Jejunoileal Stenosis and Atresia

Etiology

Multiple theories regarding the etiology of jejunoileal atresia have been studied in many animal models (eg, puppies, ewes, rabbits, and chick embryos).[19, 20, 21, 22, 23] Murine studies suggest that some forms of atresia may be hereditary and result from dysregulation of proliferation and apoptosis of the developing intestine through the fibroblast growth factor pathways.[24] To date, the best-accepted etiologic theory has been that of an intrauterine vascular accident resulting in necrosis of the affected segment, with subsequent resorption.[4, 20]

Classification

Jejunoileal defects may be divided into two broad categories, stenosis and atresia. A stenosis has an intact mesentery and is a localized narrowing of the bowel. Luminal continuity is not lost, and the stenotic portion of the bowel generally has an irregular muscularis and a thickened submucosa. Four types of jejunoileal atresias are described,[4, 20, 25, 26] representing a spectrum of severity ranging from a simple web to full atresia with loss of bowel length. This classification generally guides prognosis and therapy (see the image below).

Atresia types

In type I jejunoileal atresias, the mucosa and submucosa form a web or intraluminal diaphragm, resulting in obstruction. As in duodenal webs, a windsock effect may be evident secondary to an increase in intraluminal pressure in the proximal bowel causing a prolapse of a portion of the web into the distal part of the bowel. A mesenteric defect is not present, and the bowel length is not affected.

In type II atresias, the mesentery is intact; however, the bowel is not joined. The dilated proximal portion has a bulbous blind end connected by a fibrous cord to the blind end of the distal flattened bowel. The overall length of the small bowel is not usually shortened.

The defect in type IIIa atresias is similar to that in type II atresias, in that both types have blind proximal and distal ends; however, in type IIIa, no bridging fibrous cord is present, and a V-shaped mesenteric defect is present. The proximal blind end is usually markedly dilated and aperistaltic. The intervening bowel has undergone intrauterine resorption, and, as a result, the bowel in this category is variably shortened.

In type IIIb atresias, besides a large mesenteric defect, significant bowel shortening is noted. This lesion is also known as a Christmas tree or apple-peel deformity, because of the bowel's appearance as it wraps around a single perfusing vessel.[27, 28] The distal small bowel receives its blood supply from a single ileocolic or right colic artery because the better part of the superior mesenteric artery is absent. This deformity has been linked to prematurity, malrotation, and subsequent short-bowel syndrome, with increased morbidity and mortality.[29, 30]

A type IV atresia involves multiple small-bowel atresias of any combination of types I to III. This defect often takes on the appearance of a string of sausages because of the multiple lesions. The cause is unknown, and etiologic theories range from multiple ischemic infarcts, possibly from a more global placental insufficiency, to an early embryologic defect of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, to an inflammatory process occurring in utero.[23, 25, 31]

Diagnosis

Prenatal diagnosis of jejunoileal lesions by means of ultrasonography and prenatal screening is possible; however, the reported accuracy of prenatal ultrasonography in this setting has varied widely, and there is a need for better diagnostic criteria.[32] Whereas associated anomalies are found in 30-40% of neonates with duodenal atresias, associated anomalies are found in only 10% of neonates with jejunoileal atresias.[6]

Clinically, neonates with a proximal atresia develop bilious emesis within hours, whereas patients with more distal lesions may take longer to begin vomiting. A normal or scaphoidlike abdomen in a neonate with bilious emesis should be considered indicative of a proximal obstruction until proven otherwise. Abdominal distention is more pronounced with distal lesions.

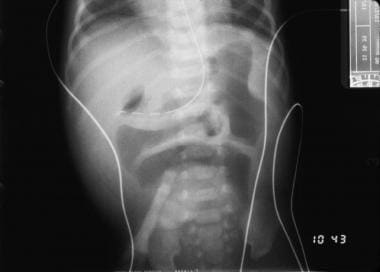

Radiography is helpful for confirming the diagnosis. With more proximal atresias, few air-fluid levels are evident with no apparent gas in the lower part of the abdomen. The more distal lesions demonstrate more air-fluid levels, though the distal intestine remains gasless (see the image below).

Although a plain radiograph can depict the presence of an obstruction, it is not the best method of showing the location of the abnormality. A barium enema may be used to define a microcolon indicative of a distal small-bowel obstruction; it is also capable of establishing the diagnosis of other causes of lower obstruction, such as Hirschsprung disease or a meconium plug. The contrast enema may also reflux into the small bowel and help define the level of a distal obstruction (see the images below).

Stenosis in a neonate is more difficult to diagnose, and it may not manifest for some time. The clinical presentation is dependent on the severity of disease, and these patients have a history of intermittent emesis and failure to thrive. An upper GI series with small-bowel follow-through is indicated in these patients.

Treatment

Preoperative care should be the same as that described for repair of duodenal lesions. Once the diagnosis is made, the patient should be fully resuscitated before surgical correction is attempted, unless a perforation or volvulus is suspected. Gastric decompression, fluid resuscitation, and thermoregulation are essential. Preoperative antibiotics should be administered.

In the operating room, a transverse supraumbilical incision affords adequate exposure of the abdominal contents. The full length of the bowel is manually explored for malrotation, other atresias, or stenoses; care is taken to keep the bowel moist and protected at all times. Malrotation should be treated with a Ladd procedure.

The length of intestine that appears functional is measured along the antimesenteric border because bowel length affects the procedure and overall prognosis. Sodium chloride solution is injected into the distal bowel and followed closely to the cecum to ensure patency. The same is done for the colon.

Once patency of the entire length of the bowel is established, the repair may proceed. The dilated proximal bulb generally does not have normal function; consequently, it should be resected up to a more suitable size to avoid problems with abnormal peristalsis postoperatively. If the bowel length is limited, a tapering enteroplasty should be considered rather than resection. An end-to-end anastomosis can then be performed (see the image below).

An alternative technique, serial transverse enteroplasty, has been used to both taper and lengthen the bowel in neonates with atresia and shortened bowel.[33, 34]In addition, in the specific case of type IV atresia with minimal remnant bowel, creative techniques such as stenting of multiple bowel segments have been performed with some success.[35]

Postoperatively, gastric drainage should continue until the return of bowel function. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) should be started shortly after surgery and continued until enteral feeds are tolerated. The baby must be closely monitored after surgery for abdominal girth, vital signs, temperature, fluid status, urine output, gastric drainage, and level of activity.

Outcome

In general, children with atresia do well postoperatively. Type IIIb atresia, by its nature, has a relatively poor prognosis, though in one long-term series, even these children had a relatively low rate of late morbidity.[36] As with duodenal atresias, mortality is primarily associated with the presence of other congenital anomalies, and birth weight.[18]

Dysmotility of the remnant bowel near sites of atresia does occur, as mentioned above, and may be related to a dysgenesis of enteric neuronal structures.[37] If the bulbous portions of atretic bowel are not resected because of limited bowel length, this dysmotility can cause late complications of stasis, bacterial overgrowth, and feeding intolerance.

The overall prognosis for patients with jejunoileal atresia depends on the amount of functional small bowel remaining after surgery. In general, 40 cm of functional bowel is considered adequate, even without an ileocecal valve; however, neonates with as little as 10 cm of small bowel have been successfully weaned from parenteral nutrition.[38]

Children with jejunoileal atresias take longer to reach full enteral nutrition than those with either duodenal or colonic atresias do, with an average time to enteral autonomy of greater than 2 weeks.[18] For optimal results, these neonates with intestinal inadequacy require careful follow-up care with surgeons, pediatric gastroenterologists, and dietitians.

0 التعليقات:

Post a Comment