Background

Bacterial abscess of the liver is relatively rare; however, it has been described since the time of Hippocrates (400 BC), with the first published review by Bright appearing in 1936. In 1938, Ochsner's classic review heralded surgical drainage as the definitive therapy; however, despite the more aggressive approach to treatment, the mortality remained at 60-80%.[1]

The development of new radiologic techniques, the improvement in microbiologic identification, and the advancement of drainage techniques, as well as improved supportive care, have reduced mortality to 5-30%; yet, the prevalence of liver abscess has remained relatively unchanged. Untreated, this infection remains uniformly fatal.

The three major forms of liver abscess, classified by etiology, are as follows:

- Pyogenic abscess, which is most often polymicrobial, accounts for 80% of hepatic abscess cases in the United States

- Amebic abscess due to Entamoeba histolytica accounts for 10% of cases [2]

- Fungal abscess, most often due to Candida species, accounts for fewer than 10% of cases

For patient education resources, see the Infections Center and the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Skin Abscess and Antibiotics.

Pathophysiology

The liver receives blood from both systemic and portal circulations. Increased susceptibility to infections would be expected given the increased exposure to bacteria. However, Kupffer cells lining the hepatic sinusoids clear bacteria so efficiently that infection rarely occurs. Multiple processes have been associated with the development of hepatic abscesses (see the image below).

Appendicitis was traditionally the major cause of liver abscess. As diagnosis and treatment of this condition has advanced, its frequency as a cause for liver abscess has decreased to 10%.

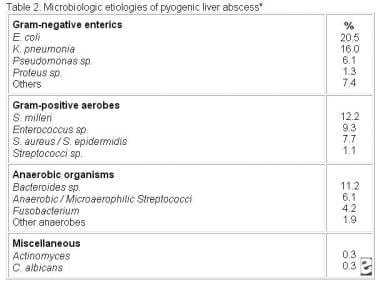

Biliary tract disease is now the most common source of pyogenic liver abscess(PLA). Obstruction of bile flow allows for bacterial proliferation. Biliary stone disease, obstructive malignancy affecting the biliary tree, stricture, and congenital diseases are common inciting conditions. With a biliary source, abscesses usually are multiple, unless they are associated with surgical interventions or indwelling biliary stents. In these instances, solitary lesions can be seen.

Infections in organs in the portal bed can result in a localized septic thrombophlebitis, which can lead to liver abscess. Septic emboli are released into the portal circulation, trapped by the hepatic sinusoids, and become the nidus for microabscess formation. These microabscesses initially are multiple but usually coalesce into a solitary lesion.

Microabscess formation can also be due to hematogenous dissemination of organisms in association with systemic bacteremia, such as endocarditis and pyelonephritis. Cases also are reported in children with underlying defects in immunity, such as chronic granulomatous disease and leukemia.

Approximately 4% of liver abscesses result from fistula formation between local intra-abdominal infections.

Despite advances in diagnostic imaging, cryptogenic causes account for a significant proportion of cases; surgical exploration has impacted this minimally. These lesions usually are solitary in nature.

Penetrating hepatic trauma can inoculate organisms directly into the liver parenchyma, resulting in pyogenic liver abscess. Nonpenetrating trauma can also be the precursor to pyogenic liver abscess by causing localized hepatic necrosis, intrahepatic hemorrhage, and bile leakage. The resulting tissue environment permits bacterial growth, which may lead to pyogenic liver abscess. These lesions are typically solitary.

PLA has been reported as a secondary infection of amebic abscess, hydatid cystic cavities, and metastatic and primary hepatic tumors. It is also a known complication of liver transplantation, hepatic artery embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, and the ingestion of foreign bodies, which penetrate the liver parenchyma. Trauma and secondarily infected liver pathology account for a small percentage of liver abscess cases.

The right hepatic lobe is affected more often than the left hepatic lobe by a factor of 2:1. Bilateral involvement is seen in 5% of cases. The predilection for the right hepatic lobe can be attributed to anatomic considerations. The right hepatic lobe receives blood from both the superior mesenteric and portal veins, whereas the left hepatic lobe receives inferior mesenteric and splenic drainage. It also contains a denser network of biliary canaliculi and, overall, accounts for more hepatic mass. Studies have suggested that a streaming effect in the portal circulation is causative.

Etiology

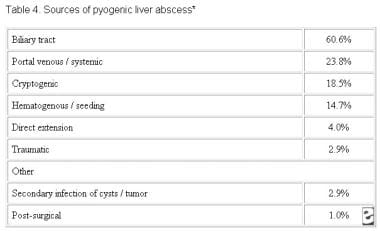

Polymicrobial involvement is common, with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae being the two most frequently isolated pathogens (see the image below). Reports suggest that K pneumoniae is an increasingly prominent cause.[4]

Enterobacteriaceae are especially prominent when the infection is of biliary origin. Abscesses involving K pneumoniae have been associated with multiple cases of endophthalmitis.

The pathogenic role of anaerobes was underappreciated until the isolation of anaerobes from 45% of cases of pyogenic liver abscess was reported in 1974. Since that time, increasing rates of anaerobic involvement have been reported, likely because of increased awareness and improved culturing techniques. The most frequently encountered anaerobes are Bacteroides species, Fusobacteriumspecies, and microaerophilic and anaerobic streptococci. A colonic source is usually the initial source of infection.

Staphylococcus aureus abscesses usually result from hematogenous spread of organisms involved with distant infections, such as endocarditis. S milleri is neither anaerobic nor microaerophilic. It has been associated with both monomicrobial and polymicrobial abscesses in patients with Crohn disease, as well as with other patients with pyogenic liver abscess.

Amebic liver abscess is most often due to E histolytica. Liver abscess is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of this infection.

Fungal abscesses primarily are due to Candida albicans and occur in individuals with prolonged exposure to antimicrobials, hematologic malignancies, solid-organ transplants, and congenital and acquired immunodeficiency. Cases involvingAspergillus species have been reported.

Other organisms reported in the literature include Actinomyces species, Eikenella corrodens, Yersinia enterocolitica, Salmonella typhi, and Brucella melitensis.

A small case series in Taiwan investigated pyogenic liver abscess as the initial manifestation of underlying hepatocellular carcinoma. In regions with a high prevalence of both pyogenic liver abscess and hepatocellular carcinoma, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of underlying hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with risk factors for the disease.[5]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The incidence of pyogenic liver abscess has essentially remained unchanged by both hospital and autopsy data. Liver abscess was diagnosed in 0.7%, 0.45%, and 0.57% of autopsies during the periods of 1896-1933, 1934-1958, and 1959-1968, respectively. The frequency in hospitalized patients is in the range of 8-16 cases per 100,000 persons. Studies suggest a small, but significant, increase in the frequency of liver abscess.

Age-related demographics

Prior to the antibiotic era, liver abscess was most common in the fourth and fifth decades of life, primarily due to complications of appendicitis. With the development of better diagnostic techniques, early antibiotic administration, and the improved survival of the general population, the demographic has shifted toward the sixth and seventh decades of life. Frequency curves display a small peak in the neonatal period followed by a gradual rise beginning at the sixth decade of life.

Cases of liver abscesses in infants have been associated with umbilical vein catheterization and sepsis.

When abscesses are seen in children and adolescents, underlying immune deficiency, severe malnutrition, or trauma frequently exists.

Sex-related demographics

While abscesses once showed a predilection for males in earlier decades, no sexual predilection currently exists. Males have a poorer prognosis from hepatic abscess than females.

Prognosis

Untreated, pyogenic liver abscess remains uniformly fatal. With timely administration of antibiotics and drainage procedures, mortality currently occurs in 5-30% of cases. The most common causes of death include sepsis, multiorgan failure, and hepatic failure.[3]

Indicators of a poor prognosis have been described since 1938 and include multiplicity of abscesses, underlying malignancy, severity of underlying medical conditions, presence of complications, and delay in diagnosis.[3]

Indicators of a poor prognosis in amebic abscess include a bilirubin level of greater than 3.5 mg/dL, encephalopathy, hypoalbuminemia (ie, serum albumin level of <2 g/dL), and multiple abscesses; all are independent factors that predict poor outcome.

An underlying malignant etiology and an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score greater than 9 increases the relative mortality by 6.3-fold and 6.8-fold, respectively.

Chen et al examined prognostic factors for elderly patients with pyogenic liver abscess.[9] Results from the study, which included 118 patients aged 65 years or older and 221 patients below age 65 years, indicated that age and an APACHE II score of 15 or greater at hospital admission were risk factors for mortality. The evidence ultimately suggested that outcomes for older patients with pyogenic liver abscess are on a par with those for younger patients. The investigators also found that in the younger patient group, there was greater frequency of males suffering from alcoholism, a cryptogenic abscess, and K pneumoniae infection.

History

The most frequent symptoms of hepatic abscess include the following (see the image below):

- Fever (either continuous or spiking)

- Chills

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Anorexia

- Malaise

Cough or hiccoughs due to diaphragmatic irritation may be reported. Referred pain to the right shoulder may be present.

Individuals with solitary lesions usually have a more insidious course with weight loss and anemia of chronic disease. With such symptoms, malignancy often is the initial consideration.

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) frequently can be an initial diagnosis in indolent cases. Multiple abscesses usually result in more acute presentations, with symptoms and signs of systemic toxicity.

Afebrile presentations have been documented.

Physical Examination

Fever and tender hepatomegaly are the most common signs. A palpable mass need not be present. Midepigastric tenderness, with or without a palpable mass, is suggestive of left hepatic lobe involvement.

Decreased breath sounds in the right basilar lung zones, with signs of atelectasis and effusion on examination or radiologically, may be present. A pleural or hepatic friction rub can be associated with diaphragmatic irritation or inflammation of Glisson capsule.

Jaundice may be present in as many as 25% of cases and usually is associated with biliary tract disease or the presence of multiple abscesses.

Complications

Complications of liver abscess may include the following:

- Sepsis

- Empyema resulting from contiguous spread or intrapleural rupture of abscess

- Rupture of abscess with resulting peritonitis

- Endophthalmitis when an abscess is associated with K pneumoniaebacteremia

Medical Care

An untreated hepatic abscess is nearly uniformly fatal as a result of complications that include sepsis, empyema, or peritonitis from rupture into the pleural or peritoneal spaces, and retroperitoneal extension. Treatment should include drainage, either percutaneous or surgical.Antibiotic therapy as a sole treatment modality is not routinely advocated, though it has been successful in a few reported cases. It may be the only alternative in patients too ill to undergo invasive procedures or in those with multiple abscesses not amenable to percutaneous or surgical drainage. In these instances, patients are likely to require many months of antimicrobial therapy with serial imaging and close monitoring for associated complications.Antimicrobial treatment is a common adjunct to percutaneous or surgical drainage.Surgical Care

Surgical drainage was the standard of care until the introduction of percutaneous drainage techniques in the mid-1970s. With the refinement of image-guided techniques, percutaneous drainage and aspiration have become the standard of care.Current indications for the surgical treatment of pyogenic liver abscess are for the treatment of underlying intra-abdominal processes, including signs of peritonitis; existence of a known abdominal surgical pathology (eg, diverticular abscess); failure of previous drainage attempts; and the presence of a complicated, multiloculated, thick-walled abscess with viscous pus.Shock with multisystem organ failure is a contraindication for surgery.Open surgery can be performed by either of the following two approaches:- A transperitoneal approach allows for abscess drainage and abdominal exploration to identify previously undetected abscesses and the location of an etiologic source

- For high posterior lesions, a posterior transpleural approach can be used; although this affords easier access to the abscess, the identification of multiple lesions or a concurrent intra-abdominal pathology is lost

A laparoscopic approach is also commonly used in select cases. This minimally invasive approach affords the opportunity to explore the entire abdomen and to significantly reduce patient morbidity. A growing literature is defining the optimal population for this mode of intervention.A retrospective chart review compared surgery versus percutaneous drainage for liver abscesses greater than 5 cm. Morbidity was comparable for the two procedures, but those treated with surgery had fewer secondary procedures and fewer treatment failures.Postoperative complications are not uncommon and include recurrent pyogenic liver abscess, intra-abdominal abscess, hepatic or renal failure, and wound infection.Consultations

Obtain an interventional radiology consultation as soon as the diagnosis is considered to allow rapid collection of cavity fluid and the potential for early therapeutic drainage of abscess.Immediately seek a consultation with a general surgeon if the source of the abscess is a known underlying abdominal pathology or in cases with peritonitis. In cases undergoing percutaneous drainage, seek the involvement of a general surgeon if drainage of the abscess cavity is unsuccessful.Gastroenterology involvement may be useful after successful drainage to evaluate for underlying gastrointestinal disease using colonoscopy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).Infectious disease consultation should be considered in complicated cases and when the involved pathogens are unusual or difficult to treat, such as in fungal abscesses.Long-Term Monitoring

Aggressively seek an underlying source of the abdominal pathology.Perform weekly serial computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound examinations to document adequate drainage of the abscess cavity. Continue radiologic evaluation to document progress of therapy after discharge.Drain care may be required. Maintain drains until the output is less than 10 mL/day.Monitor fever curves. Persistent fever after 2 weeks of therapy may indicate the need for more aggressive drainage.For patients with an underlying malignancy, definitive treatment, such as surgical removal of the mass, should be pursued if at all possible.Patients will require prolonged parenteral antimicrobial therapy that may continue after discharge. Monitoring of medication levels, renal function, and blood counts may be needed. Enteral nutrition is the preferred route unless it is clinically contraindicated.Medication Summary

Until cultures are available, the choice of antimicrobial agents should be directed toward the most commonly involved pathogens. Regimens using beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, carbapenems, or second-generation cephalosporins with anaerobic coverage are excellent empiric choices for the coverage of enteric bacilli and anaerobes. Metronidazole or clindamycin should be added for the coverage of Bacteroides fragilis if other employed antibiotics offer no anaerobic coverage.Amebic abscess should be treated with metronidazole, which will be curative in 90% of cases. Metronidazole should be initiated before serologic test results are available. Patients who do not respond to metronidazole should receive chloroquine alone or in combination with emetine or dehydroemetine.Systemic antifungal agents should be initiated if fungal abscess is suspected and after the abscess has been drained percutaneously or surgically. Initial therapy for fungal abscess is currently amphotericin B. Lipid formulations may offer some benefit in that the complexing of drug to lipid moieties allows for concentration in hepatocytes. Further investigation is required for definitive proof. Cases of successful fluconazole treatment after amphotericin failure have been reported; however, its use as an initial agent is still being studied.Ultimately, the organisms isolated and antibiotic sensitivities should guide the final choice of antimicrobials.Duration of treatment has always been debated. Short courses (2 wk) of therapy after percutaneous drainage have been successful in a small series of patients; however, most series have reported recurrence of abscess even after more prolonged courses. Currently 4-6 weeks of therapy is recommended for solitary lesions that have been adequately drained. Multiple abscesses are more problematic and can require up to 12 weeks of therapy. Both the clinical and radiographic progress of the patient should guide the length of therapy.Antibiotics

Class Summary

Empiric antimicrobial therapy must be comprehensive and should cover all likely pathogens in the context of the clinical setting.Meropenem (Merrem)

Bactericidal broad-spectrum carbapenem antibiotic that inhibits cell-wall synthesis. Effective against most gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.Has slightly increased activity against gram negatives and slightly decreased activity against staphylococci and streptococci species compared to imipenem.Imipenem and cilastatin (Primaxin)

For treatment of multiple organism infections in which other agents do not have wide-spectrum coverage or are contraindicated due to potential for toxicity.Cefuroxime (Ceftin)

Second-generation cephalosporin maintains gram-positive activity that first-generation cephalosporins have; adds activity against Proteus mirabilis,Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Condition of patient, severity of infection, and susceptibility of microorganism determine proper dose and route of administration.Cefotetan (Cefotan)

Second-generation cephalosporin indicated for infections caused by susceptible gram-positive cocci and gram-negative rods.Dosage and route of administration depends on condition of patient, severity of infection, and susceptibility of causative organism.Cefoxitin (Mefoxin)

Second-generation cephalosporin indicated for gram-positive cocci and gram-negative rod infections. Infections caused by cephalosporin-resistant or penicillin-resistant gram-negative bacteria may respond to cefoxitin.Cefaclor (Ceclor)

Second-generation cephalosporin indicated for infections caused by susceptible gram-positive cocci and gram-negative rods.Determine proper dosage and route based on condition of patient, severity of infection, and susceptibility of causative organism.Clindamycin (Cleocin)

Lincosamide for treatment of serious skin and soft tissue staphylococcal infections. Also effective against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci (except enterococci). Inhibits bacterial growth, possibly by blocking dissociation of peptidyl t-RNA from ribosomes causing RNA-dependent protein synthesis to arrest.Metronidazole (Flagyl)

Imidazole ring-based antibiotic active against various anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. Used in combination with other antimicrobial agents (except forClostridium difficile enterocolitis).Antifungal agents

Class Summary

Their mechanism of action may involve an alteration of RNA and DNA metabolism or an intracellular accumulation of peroxide that is toxic to the fungal cell.Amphotericin B (AmBisome)

Produced by a strain of Streptomyces nodosus; can be fungistatic or fungicidal. Binds to sterols, such as ergosterol, in the fungal-cell membrane, causing intracellular components to leak with subsequent fungal-cell death.Fluconazole (Diflucan)

Synthetic oral antifungal (broad-spectrum bistriazole) that selectively inhibits fungal cytochrome P-450 and sterol C-14 alpha-demethylation.

0 التعليقات:

Post a Comment