Background

A Meckel diverticulum is an embryologic abnormality that is part of a spectrum of anomalies known as yolk stalk or omphalomesenteric duct remnants (see the images below). Fabricus Hildanus first described a Meckel diverticulum in 1598. In 1809, Johann Meckel, an anatomist, described this anomaly in detail. He identified the origin of the diverticulum as the omphalomesenteric duct and emphasized that this anatomic abnormality was a potential cause of disease. In 1904, Salzer became the first to identify ectopic mucosa within the diverticulum.

Newborn infant with persistent omphalomesenteric remnant, which is being resected to prevent obstruction and to close umbilical defect. Image courtesy of Kenneth Gow, MD, BSc, MSc, FRCSC, FACS, FAAP.

Newborn infant with persistent omphalomesenteric remnant, which is being resected to prevent obstruction and to close umbilical defect. Image courtesy of Kenneth Gow, MD, BSc, MSc, FRCSC, FACS, FAAP. Large Meckel diverticulum on antimesenteric surface of terminal ileum. Image courtesy of Richard A Falcone, Jr, MD.

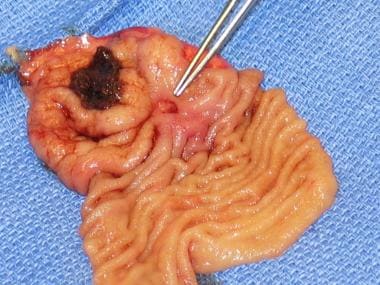

Large Meckel diverticulum on antimesenteric surface of terminal ileum. Image courtesy of Richard A Falcone, Jr, MD.

Depending on the type of anomaly, patients may be completely asymptomatic or may present with bleeding, inflammation, obstruction, or umbilical drainage. (SeePresentation.) Treatment is surgical. (See Treatment.)

Anatomy

The omphalomesenteric (vitelline) duct typically arises from a point about 60 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve in adults. The Meckel diverticulum is an antimesenteric structure but receives its blood supply from the mesentery of the ileum. Thus, a typical feeding vessel (vitelline artery, also described as the omphalomesenteric mesentery) may be identified. It crosses from the mesentery of the ileum, across the intestine itself, and along the length of the diverticulum. This feeding vessel must be individually clipped and divided during a laparoscopic Meckel diverticulectomy.

Meckel diverticula may contain ectopic mucosa. The two most common types of ectopic mucosa are gastric and pancreatic. As many as 50% of all diverticula contain gastric mucosa, whereas 5% contain pancreatic mucosa. Ectopic gastric mucosa results in secretion of acid onto adjacent ileal mucosa, causing ulceration and bleeding.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology varies depending on the etiology of symptoms (seePresentation). A 16-year review of symptomatic Meckel diverticula in children revealed that 55.5% of patients had gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, 14.2% had intestinal obstruction, 15.8% presented with peritonitis, and 14.2% had umbilical drainage.[1]

Etiology

The existence of a Meckel diverticulum or one of its variants is due to simple embryology. The yolk sac of the developing embryo is connected to the primitive gut by the yolk stalk or vitelline (ie, omphalomesenteric) duct. This structure typically regresses between weeks 5 and 7 of fetal life. If this process of regression fails, various anomalies can occur. This spectrum of defects includes a Meckel diverticulum, a fibrous cord attaching the distal ileum to the abdominal wall, an umbilical-intestinal fistula, a mucosa-lined cyst, or an umbilical sinus. Various possible complications are associated with different omphalomesenteric remnants (see the image below).

Diagram depicting possible complications associated with different omphalomesenteric remnants. Meckel diverticula are symptomatic in 4-35% of patients. Infants and young children are more likely to present with symptoms. (A) Meckel diverticulitis. These are true diverticula, which usually become inflamed from obstruction. (B) Meckel diverticula, which may contain ectopic gastric, pancreatic, or colonic mucosa. In gastric ectopic mucosa, acid secreted from parietal cells erodes adjacent intestinal mucosa, generating ulcers at base of diverticulum. (C) Omphalomesenteric (vitelline) duct, which connects primitive gut to yolk sac. It normally regresses between weeks 5 and 7 of fetal life. When failed regression results in fibrous band, midgut may volvulate around it. (D) Fibrous bands, which also produce abnormal peritoneal spaces through which internal hernia may result. (E) Omphalointestinal fistula. If patent connection persists between intestine and umbilicus, entity is recognized as omphalointestinal fistula. (F) Persistent fibrous cord with cyst. Failed regression of vitelline duct may also lead to umbilical polyps, umbilical sinus, or umbilical cyst. Image courtesy of Jaime Shalkow, MD.

Diagram depicting possible complications associated with different omphalomesenteric remnants. Meckel diverticula are symptomatic in 4-35% of patients. Infants and young children are more likely to present with symptoms. (A) Meckel diverticulitis. These are true diverticula, which usually become inflamed from obstruction. (B) Meckel diverticula, which may contain ectopic gastric, pancreatic, or colonic mucosa. In gastric ectopic mucosa, acid secreted from parietal cells erodes adjacent intestinal mucosa, generating ulcers at base of diverticulum. (C) Omphalomesenteric (vitelline) duct, which connects primitive gut to yolk sac. It normally regresses between weeks 5 and 7 of fetal life. When failed regression results in fibrous band, midgut may volvulate around it. (D) Fibrous bands, which also produce abnormal peritoneal spaces through which internal hernia may result. (E) Omphalointestinal fistula. If patent connection persists between intestine and umbilicus, entity is recognized as omphalointestinal fistula. (F) Persistent fibrous cord with cyst. Failed regression of vitelline duct may also lead to umbilical polyps, umbilical sinus, or umbilical cyst. Image courtesy of Jaime Shalkow, MD.Epidemiology

Meckel diverticula are found in approximately 2% of the population. The prevalence of symptomatic Meckel diverticula is estimated to be 4-35% of the at-risk population, depending on the age group studied. More than 60% of patients who develop symptoms from this anomaly are aged 2 years or younger.

Prognosis

Patients typically do not have further bleeding episodes once the Meckel diverticulum and ectopic gastric mucosa have been excised. Patients who require exploratory laparotomy for bowel obstruction are at risk for adhesive bowel obstruction in the future.

History and Physical Examination

Meckel diverticula and omphalomesenteric variants may result in various clinical presentations, including painless bleeding, bowel obstruction, Meckel diverticulitis, and umbilical drainage.

Painless bleeding

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage is the most common symptom in patients with a symptomatic Meckel diverticulum. The mean age is 2 years, though this problem may occur in older children and even adults. The bleeding is typically painless; it can be massive and may require blood transfusion. Other causes of bleeding that may occur in this same age group include anal fissure, juvenile retention polyps, hemangiomas, peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and primary hematologic disorders.

Bleeding is secondary to ulcerated ileal mucosa resulting from ectopic gastric mucosa that is contained within the Meckel diverticulum. The gastric mucosa secretes acid, which results in ulceration of the adjacent normal ileal mucosa. (See the images below.)

Meckel diverticulum has been opened after resection, revealing ulcer and ectopic tissue, as indicated by forceps. Image courtesy of Richard A Falcone, Jr, MD.

Meckel diverticulum has been opened after resection, revealing ulcer and ectopic tissue, as indicated by forceps. Image courtesy of Richard A Falcone, Jr, MD.Bowel obstruction

In children, obstruction is the second most common symptom in patients with symptomatic Meckel diverticula and occurs in approximately 25% of symptomatic patients. Obstruction can be caused by several mechanisms. Volvulus of the small intestine may occur around a Meckel fibrous band attached to the umbilicus. Intussusception of the Meckel diverticulum may also result in intestinal obstruction. Incarceration of the diverticulum in a hernia, known as a Littre hernia, is a third cause of obstruction.

Another cause of bowel obstruction is entrapment of small bowel beneath the blood supply of the diverticulum, also known as a mesodiverticular band.

Meckel diverticulitis

Diverticulitis may occur in as many as 20% of patients with complications from a Meckel diverticulum. Meckel diverticulitis is commonly misdiagnosed as acute appendicitis. Inflammation of the diverticulum may be due to obstruction of the lumen, which is analogous to the pathophysiology of acute appendicitis. Progression of such inflammation may lead to perforation and peritonitis. The possibility of Meckel diverticulitis underscores the need to explore the distal small bowel in patients with suspected appendicitis when a normal appendix is found.

Umbilical drainage

Drainage of succus entericus or feculent discharge is due to a patent omphalomesenteric duct, whereas clear drainage should prompt a search for a urachal remnant.

Umbilical mass or infection

Omphalomesenteric duct remnants may persist as an actual cystic structure, typically just beneath the umbilicus. This structure may be palpable upon physical examination or, if infected or ruptured, may lead to inflammatory changes in the umbilicus.

Perforation

Because a Meckel diverticulum may contain ectopic gastric mucosa, the bordering small intestine mucosa may ulcerate, which may cause actual perforation of the intestine. This leads to peritonitis and free intraperitoneal air, which can be seen on plain abdominal films. The intestine may also perforate if a closed loop bowel obstruction is allowed to progress to bowel wall necrosis.

0 التعليقات:

Post a Comment