ackground

Constipation is an extremely common problem in the pediatric population. Most patients can be treated with mild measures (eg, dietary changes and laxatives). However, a significant number of patients have severe constipation and require more aggressive treatments, and some even need surgery. Most have functional (idiopathic) constipation, which is associated with a wide spectrum of severity. A small number of patients have very severe bowel dysmotility and overlap with the group of patients considered to have intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

In addition to patients with functional constipation, patients who have undergone surgery for anorectal malformations, as well as those with Hirschsprung disease,[1, 2] can suffer from severe constipation and incontinence. Management of patients with these surgical problems has greatly informed the care of patients with idiopathic constipation.

If the patient is not toilet-trained by age 3 years and the family wishes the child to be rendered clean, the clinician can offer an artificial way to keep the patient clean and socially acceptable. This regimen essentially involves teaching the family and patient how to clean the colon once a day with an enema and how to manipulate the colonic motility with diet, medications, or both when necessary to ensure that the patient does not pass stool between enemas.

Understanding the difference between fecal incontinence and the phenomenon known as overflow pseudoincontinence or encopresis (which is a sequela of a severe inertia of the rectosigmoid) is vital because management approaches to these two types of patients differ significantly.

For patients who lack the capacity for voluntary bowel movements and thus cannot voluntarily empty their colons, fecal incontinence requires a mechanical bowel management regimen that involves daily enemas. Patients with incontinence due to severe constipation may have overflow pseudoincontinence; once their constipation is managed, they may be able to have voluntary bowel movements. Such patients require a bowel management regimen that involves laxatives, which help them regularly and voluntarily empty their colon.

Medical treatment with enemas, laxatives, and medications has traditionally been used for patients with soiling, with varying degrees of success.[3, 4] These treatments are often used without a specific rationale in an indiscriminate manner that often reflects a lack of understanding of the difference between patients with overflow pseudoincontinence and those with real fecal incontinence.

Bowel management with an organized protocol that is implemented by a thoughtful team of physicians and nurses can have a dramatic impact on a patient with fecal incontinence. Likewise, bowel management in a patient with overflow pseudoincontinence can treat the impaction, avoid constipation, and promote the conditions needed for fecal continence.

The process of bowel management in patients with fecal incontinence is one of trial and error. With the described protocol, the vast majority of patients have success and can live reasonably normally with a good quality of life.

Better understanding of the causes of poor colonic motility will dramatically improve its treatment. The ideal management for these patients would be pharmacologic agents that can induce a single colonic contraction with complete emptying of the colon and then keep the colon quiescent for the next 24 hours. If such a regimen existed, incontinence would be cured.

Most likely, there are histologic abnormalities that explain slow colonic motility but remain undetected with current histologic techniques. Also, motility studies of the colon may eventually reach a degree of perfection that will make them more reliable and more useful from a clinical point of view. Ideally, such studies could clearly show whether laxative antegrade enemas or resection of a part of the colon should be part of the treatment plan. Eventually, an understanding of genetics will play a role in the prevention of this condition. Future developments in these areas will dramatically affect the quality of life in many children.

For complete information on these topics, see Constipation and Pediatric Constipation.

Pathophysiology

Bowel motility is one of the most complex and sophisticated functions in the human body. The colon absorbs water and functions as a reservoir. Liquid waste delivered by the small bowel into the cecum becomes solid stool in the descending and sigmoid colon.

The colon has a slow motility; peristalsis seems to be less active in its distal portions. Normally, the rectosigmoid remains quiet for periods of 24-48 hours. Active peristaltic waves then develop, indicating that the rectosigmoid must be emptied. This development is perceived by the individual, who then has the capacity to voluntarily retain the stool up to a point or to empty it, depending on social circumstances.

To achieve fecal continence, the following three components are necessary:

- Sensation within the rectum

- Reliable motility of the colon

- Good voluntary muscle or sphincter control

Children who have anorectal malformations lack some or all of these essential components. Children who have undergone pelvic surgery for Hirschsprung disease may have lost some of these components as a consequence of their surgical treatment (most importantly, their sphincters and dentate line).

All patients born with anorectal malformations (except those with pure rectal atresia, which is rare) are missing the anal canal; thus, they do not experience the exquisite sensation in this area that is very important for continence. They lack the intrinsic sensation associated with stool or gas passing through the rectum. Therefore, they may soil themselves unknowingly.

In a child with an anorectal malformation whose rectum has been correctly placed within the sphincter mechanism, distention of the rectum stretches the voluntary muscles that surround the rectum and gives the child proprioception, which is another vital component of continence. The sphincter mechanism in children with imperforate anus varies across a broad spectrum ranging from a mechanism similar to that observed in a child with bowel continence to a near-total absence of muscles in the perineum.

In patients with anorectal malformations, the presence of a preserved rectal reservoir plays a pivotal role. Poorly developed muscles, which are often associated with a hypodeveloped sacrum or spinal and vertebral problems (eg, hemivertebrae, tethered cord, or myelomeningocele), clearly contribute to the potential for fecal and urinary incontinence.

Patients with anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung disease have abnormal peristaltic waves in the colon, which result either in stagnant stool or in an overactive colon. The child then develops constipation or overflow pseudoincontinence (encopresis). Alternatively, a very active colon may provoke a constant passing of stool, which may significantly interfere with bowel continence.

Etiology

Functional constipation is an inability to pass or difficulty with passing stool regularly and efficiently. The etiology of this condition is unknown. It is by far the most common defecation disorder and the most common colonic motility disorder in children. Constipation affects an enormous pediatric population and represents a very common cause for surgical consultation.

Constipation is relevant not only because it affects millions of patients but also because it is extremely incapacitating in its most serious form. It can produce overflow pseudoincontinence, or encopresis (with soiling), which is to be distinguished from true fecal incontinence. Also, the most serious type of constipation cannot be differentiated from intestinal pseudo-obstruction, a very serious motility disorder that carries a significant morbidity.

Even though the cause of this condition is unknown, the literature presents many potential causes for the disease, most of which have no solid scientific basis. Many publications discuss dietary disorders as a cause of constipation. Different types of food have either a laxative or constipating effect on the body.

Diet is certainly important for regulating colonic motility; however, the therapeutic value of diet is negligible in the most serious forms of constipation. Thousands of patients with mild forms of constipation are successfully managed with dietary measures alone. However, patients in whom surgery is indicated have a much more serious form of this condition that does not respond to dietary treatment alone.

History

Constipation after surgery

Children with fecal incontinence after imperforate anus repair can be divded into two categories: those with slow motility and those with fast motility.

Those with constipation (ie, slow motility) after this repair have usually undergone a procedure in which the rectum was preserved (eg, anoplasty, posterior sagittal anorectoplasty, or sacroperineal pull-through procedure); the vast majority of patients fall into this category. Those with diarrhea (ie, fast motility) after the repair have usually undergone a procedure in which the rectum—and sometimes the sigmoid colon—was resected (eg, abdominoperineal pull-through procedures or endorectal resections). Occasionally, the child has lost a portion of the colon for another reason or has a diarrhea-producing condition.

The patient’s capacity for fecal continence (ie, the ability to hold stool voluntarily) varies according to the type of anorectal malformation with which the patient was born. High malformations are often accompanied by poor muscles, whereas low malformations are usually associated with good muscles.

The degree of hypodevelopment of the sacrum and the presence of associated spinal anomalies contribute to the degree of fecal continence. For instance, a child with a high anomaly and near-normal muscles, sacrum, and spine has a good chance of achieving fecal continence.

Children who have undergone surgery for Hirschsprung disease often have postoperative constipation, but some have hypermotility. A small group of patients have fecal incontinence as a sequela of the original pelvic operation related to the degree of preservation of their anal canal and their sphincter mechanism.

Functional constipation

Functional constipation is a self-perpetuating and self-aggravating disease. A patient who has a certain degree of constipation that is inadequately treated only partially empties the colon throughout the day, leaving larger and larger amounts of stool inside the rectosigmoid, and this results in greater degrees of megasigmoid. Most surgeons accept that the dilatation of a hollow viscus produces poor peristalsis, which leads to dilatation. This explains why constipation is due to fecal retention, which produces megacolon that exacerbates the constipation.

In addition, the passage of large, hard pieces of stool may produce painful anal lacerations (fissures), which render the patient reluctant to have bowel movements. If the constipation does not receive proper treatment, it worsens and becomes an increasingly serious problem.

The condition is mostly incurable, which means that these patients must be monitored for life. Unfortunately, treatments are frequently administered on a temporary rather than an ongoing basis. Once the treatments are tapered or interrupted, recurrence typically ensues. This creates a great deal of frustration for patients and parents and may contribute to the well-known pattern of patients who seek a solution from many different doctors or clinics.

Another controversy involves symptom onset. Many doctors believe that this problem starts during toilet training. Although symptoms become more evident at that time, the motility disorder is often present at birth. Breastfed babies may not show symptoms, because of the well-known laxative effect of human breast milk. When breastfeeding is discontinued and the patient receives formula and other foods, the symptoms become obvious. Babies who have constipation problems while breastfeeding are likely to have severe constipation that will only worsen over time. Some of these patients need to be checked for Hirschsprung disease.

Many times, parents report that symptoms began in the patient’s preschool years. However, specific inquiries regarding bowel movement patterns since birth often reveal that the constipation actually started very early in life. Typically, the parents remember the first fecal impaction episode most vividly and refer to that event as the initiation of symptoms.

The definition of constipation is another problem. Many pediatricians believe that healthy individuals can go 2-3 days without a bowel movement throughout their lives without having any significant implications. This principle holds true for many individuals; however, when it is applied to a patient who has demonstrated functional constipation, it can interfere with effective treatment.

Constipation in infants is manifested by difficult and sometimes painful bowel movements, the presence of hard stool, the passage of bloodstained large pieces of stool, and periods of 2-3 days without passing stool. When these babies receive laxatives, the parents often have to increase the amount of laxatives administered to the point of producing diarrhea before the baby can pass stool. Even with liquid stool, parents describe the babies as being incapable of having bowel movements without some form of rectal stimulation.

The presence of a fissure is the first sign of trouble because it produces painful bowel movements, which tend to make the patient retain stool. Holding the stool for several days produces stool retention, which leads to hardening of the stool. However, the patient eventually passes a larger and harder piece of stool that reopens the fissure, creating a vicious circle.

Mild forms of this condition can usually be successfully treated by a pediatrician, who may prescribe a high-fiber diet, foods that act as laxatives, or both. If the diet does not correct the problem, then the pediatrician usually prescribes stool softeners, active-ingredient laxatives, or both. Stool softeners soften the stool, but do not help it come out, often leading to worsening of the soiling. Laxatives are usually administered in the recommended dosages, which are successful in many patients but not in all patients; this is understandable, given the wide spectrum of severity in this condition. Usually, in the severe cases, not enough laxatives were prescribed.

Fecal impaction is a stressful event characterized by retention of stool for several days, crampy abdominal pain, and, occasionally, tenesmus. A rectal examination discloses the presence of a large mass of rock-hard stool located very low in the rectum. When laxatives are prescribed to a patient with fecal impaction, the result is an exacerbation of the abdominal pain with severe cramping and, occasionally, vomiting. This is a consequence of increased colonic peristalsis (produced by the laxative) acting against a colonic obstruction (produced by the fecal impaction). It is for this reason that a cleanout is required before a stimulant laxative is started.

Despite the impaction, the patient may pass liquid stool, which is a phenomenon known as paradoxical diarrhea; the liquid stool passes around the solid fecal matter, but the impaction persists. Abdominal radiography can clarify this situation.

Most practitioners recognize and diagnose constipation upon learning that a patient has difficulty passing stool or that a patient has not passed stool in 1-3 days. Another form of constipation that is not recognized by most physicians is characterized by multiple bowel movements throughout the day, consisting of very small amounts of stool. The stool is very sticky and thick and eventually becomes only a smearing or soiling of the underwear. This should also be considered constipation.

Soiling of the underwear without the patient’s awareness is an ominous sign of bad constipation. If a patient who should have achieved bowel control soils his or her underwear day and night and does not have spontaneous bowel movements, he or she has overflow pseudoincontinence (ie, encopresis). Children with this condition behave as fecally incontinent individuals. When the constipation is adequately treated, the great majority of these pseudoincontinent children regain bowel control.

The diagnosis is a clinical one. The symptoms described above are very reliable in establishing the diagnosis. In addition, if a patient presents with symptoms similar to those described above, functional constipation is likely. Patients with untreated Hirschsprung disease do not soil themselves; in addition, without surgical treatment, Hirschsprung disease causes significant symptoms with distention and enterocolitis, and such patients are frequently malnourished.

Patients with functional constipation do not have real enterocolitis. They occasionally experience episodes of distention and vomiting, similar to what is observed in enterocolitis. However, they actually have fecal impaction and an added picture of viral gastroenteritis that causes severe, crampy, abdominal pain and diarrhea around the impaction. Patients with Hirschsprung disease who experience actual enterocolitis become extremely toxic and lethargic and may die.

Physical Examination

Physical examination may reveal a left-lower-quadrant mass, which represents a sigmoid colon filled with impacted stool.

Examination of the rectum is vital to determine impaction. Also, in patients who have undergone surgery, the clinician must rule out the presence of a postoperative anal or rectal or colonic stricture.

The location and caliber of the anus should be evaluated. Patients with anorectal malformations may have an anteriorly placed anus that is incorrectly situated. Previously undiagnosed rectovestibular or rectoperineal fistulae in female patients have been reported. Congenital anal or rectal stenosis, which is very rare, may miss being detected in the newborn period.

Radiography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The most important radiologic study for the evaluation of patients with bowel problems is plain abdominal radiography. This helps the clinician determine how much stool is present in the colon and helps confirm or refute the history of either constipation or diarrhea.

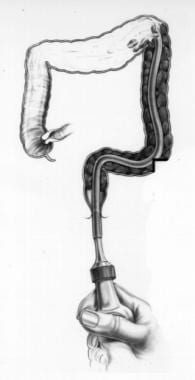

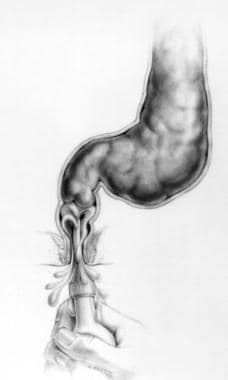

A contrast enema should be performed to evaluate the patient’s colonic anatomy. Findings from this study help the clinician infer whether patients are likely to have slow motility or fast motility. In a patient with functional constipation, the colon (particularly the rectosigmoid) may be dilated, redundant, or both. If the contrast study reveals a straight colon on the left side, the rectosigmoid was resected during imperforate anus repair, and the patient has fast motility (see the first image below). If the contrast study reveals a megarectosigmoid, the rectum was preserved during the original operation, and the patient has slow motility (see the second image below).

A contrast enema should be performed with hydrosoluble material (never barium). It is the most valuable study for confirming the diagnosis of functional constipation. The dilatation of the colon extends all the way down to the level of the levator mechanism, which is recognized because it coincides with the pubococcygeal line. The lack of dilatation of the rectum below the levator mechanism (pubococcygeal line) should not be interpreted as a transition zone or nondilated aganglionic bowel.

Under normal circumstances, the anal canal and the part of the rectum below the levator mechanism are collapsed by the effect of the striated muscle tone from the sphincter mechanism. The rectum above the anal canal is extremely dilated, as is the sigmoid. The contrast enema in patients with functional constipation reveals different degrees of dilatation of the rectosigmoid, as is expected in a spectrum-type condition. Most interestingly, a dramatic size discrepancy is noted between a normal transverse and descending colon and an extremely dilated megarectosigmoid.

These changes are actually the reverse of what is observed in patients with Hirschsprung disease. The colon in a patient with Hirschsprung disease is dilated only proximal to the aganglionic segment, which remains nondilated.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an excellent tool for determining whether a patient who has previously undergone imperforate anus repair has a correctly located rectum. A specific MRI protocol that involves placement of a rubber tube in the rectum reveals whether the rectum was placed within the sphincter mechanism.

MRI of the spine is sometimes needed to evaluate for an associated spinal condition as the cause of the constipation.

Anorectal and Colonic Manometry

Anorectal manometry is used by many practitioners.[5] According to the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN), the main indication for performing anorectal manometry in the evaluation of intractable constipation is to evaluate for the presence of the rectoanal-inhibitory reflex.[6]

Traditionally, anorectal manometry is performed by placing a balloon in the rectum while measuring the pressure of the anal canal. Under normal circumstances, when the rectal balloon is inflated, the pressure within the anal canal decreases; this is described as the anorectal reflex. Pressure that does not decrease in the anal canal is considered abnormal and is said to be a sign of lack of relaxation of the internal sphincter. This is also considered diagnostic for Hirschsprung disease; however, it must be confirmed by rectal biopsy. Manometry can also diagnose anal sphincter achalasia, a condition that causes constipation and that can be treated with injection of botulinum toxin in the anal canal.

Colonic manometry, which measures propagation of peristalsis through the colon, is valuable in determining which specific part of the colon is working and which is not and can help guide decisions such as which laxatives may work, whether an antegrade option (cecostomy or Malone) might be useful, and whether a colonic resection is required.

Histologic Findings

Rectal biopsies are usually performed with the specific purpose of ruling outHirschsprung disease. The study is usually unnecessary when the clinical picture and the radiologic findings are characteristic of functional constipation.

Rectal biopsies are performed if the contrast enema reveals findings that suggest aganglionosis or if the patient behaves in a way that is clinically similar to a patient with Hirschsprung disease. If the patient has episodes of enterocolitis and does not soil, Hirschsprung disease is suspected. If the rectal examination reveals an empty rectum and the patient is still impacted above the reach of the finger, consider Hirschsprung disease and perform a biopsy.

Treatment of Postoperative Constipation and Diarrhea

Recognizing the different types of fecal incontinence is vital in the treatment of a patient with fecal incontinence after surgery for anorectal malformations or Hirschsprung disease. The clinician must learn how to evaluate these patients, how to recognize the specific type of fecal incontinence, and how to implement the best treatment modality.

If true anatomically based fecal incontinence is determined to be present, the first step is teaching the family and patient how to clean the colon with an enema. In patients with slow motility, this is a challenge. The correct enema type and amount needed to clean the colon must be determined. Keeping the colon quiet for 24 hours until the next enema is not difficult, because the patient has slow motility.

In patients with fast motility, cleaning the colon with an enema is easy. The challenge in these patients is to keep the colon quiet for 24 hours until the next enema. Controlling the hypermotility requires a constipating diet and medications such as loperamide and water-soluble fiber.

These patients must be seen regularly. The treatment process is one of trial and error, and the vast majority of patients can have success with the bowel management program within 1 week.

The problem of overflow pseudoincontinence must be suspected in the evaluation of a patient born with a benign anorectal malformation, which is associated with a good functional result. These patients often experience severe constipation that has not been properly treated and present with what the family believes is fecal incontinence.

Such a patient must first be disimpacted. Then, over several days, bowel control must be determined. If the patient is truly incontinent and constipated, bowel management with enemas is necessary. On the other hand, if the patient has bowel control, they need a determined dose of laxative given on a permanent basis with an option for a sigmoid resection, which may make management easier by significantly decreasing the laxative requirements.

Constipation in patients with incontinence

Patients with constipation (ie, slow motility) are much easier to treat than those with diarrhea. The rectum normally remains quiet for 24-48 hours, after which the rectosigmoid contracts and empties during a normal episode of defecation. The rectosigmoid then remains quiet for 1-2 days.

To manage constipation, daily cleaning of the colon with an enema is used. If the rectosigmoid has been preserved, as is the case with a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (see Imperforate Anus, Surgical Perspective), the patient often experiences varying degrees of constipation and the inability to empty the colon completely in a single bowel movement. These patients require large enemas and no specific dietary restrictions or medications.

The child sits on the toilet for 30-45 minutes usually in the evening. Saline enemas are used with the addition of glycerin or soap to make it more concentrated. An enema that is correctly administered on a daily basis should result in a bowel movement followed by a period of 24 hours of complete cleanliness.

The volume of the enema is determined by trial and error. A No. 20-24 Foley catheter is lubricated and gently introduced through the anus (see the images below). The Foley balloon is inflated to act as a plug.

If the child soils at any point during the following 24 hours, the bowel washout was likely incomplete, and a more aggressive enema is required. The volume of saline can be increased, or more additives can be used. Sometimes an enema is too strong and causes the accident. An abdominal radiograph helps determine which is the case. The program is individualized, and parents and children learn to examine the consistency and amount of stool obtained after the enema to determine whether it was effective.

Diarrhea in patients with incontinence

If the rectosigmoid was resected, as it would have been in an abdominoperineal procedure or an endorectal dissection (a procedure some surgeons in the past used to repair imperforate anus), the patient has diarrhea (ie, fast motility) as a consequence of the loss of the section of the colon most responsible for water absorption, and thus continuously passes stool. These patients are also very sensitive to foods that provoke liquid stools.

Liquid stool is problematic in children with anorectal malformations. This type of stool does not distend the rectum and leaks out without the child’s knowledge. The goal of instituting bowel management in these patients is to have them form solid stool so that they are able to feel something with the voluntary muscles.

Rapid transit of stool results in frequent episodes of diarrhea. Stool passes so rapidly from the cecum to the descending colon that these patients are unable to remain clean, even after administration of an enema. The bowel management program consists of teaching parents and patients a method of cleaning the colon completely every day and simultaneously determining a method to keep the colon quiet for 24 hours.

To decrease diarrhea, constipating diets and medications (eg, loperamide) and water-soluble fiber are used to slow down the colon. A small daily enema is required. Keeping the colon clean is relatively easy; keeping it quiet between enemas is difficult.

Incontinence vs overflow pseudoincontinence

Distinguishing between fecal continence and fecal incontinence is vital. Many patients present with severe constipation but are fecally continent. They may demonstrate signs of overflow pseudoincontinence if their colon is filled with stool and if they are impacted. Constipation management with laxatives can solve this problem.

Patients who are incontinent and have constipation are very different. No matter how great the amount of laxatives administered, they cannot empty their colon with any control. These patients require daily enemas to clean the colon completely.

Making this distinction is sometimes difficult. Occasionally, patients present with incontinence and severe constipation. Once the impaction is managed, they are continent if constipation is avoided by use of laxatives.

Treatment of Functional (Idiopathic) Constipation

Measures for mild constipation

In patients with mild forms of constipation, pediatricians and pediatric gastroenterologists use dietary measures. If this is not sufficient, stool softeners are administered. If stool softeners are not effective, stimulant laxatives are administered. Many such patients are referred to psychologists and subjected to behavior modification and biofeedback treatment. Many of these patients can benefit from bowel management techniques.

Trial of medical management

The protocol of treatment in patients with severe forms of functional constipation includes a trial of medical management (stimulant laxatives). If patients do not respond to this treatment, then a specific type of operation may be needed.

Almost always, the patient previously received less laxative than was required. The dosage is adjusted daily, and abdominal films are obtained every day to objectively evaluate the degree of fecal impaction until the correct amount of laxatives is determined.

In a study involving 44 children with refractory idiopathic constipation, Russell et al found that a structured bowel management program, based on assessment of clinical response and daily radiographs in a pediatric colorectal center with longitudinal follow-up, was effective and led to an 82% reduction in hospital admissions.[7]

Disimpaction

When patients come for consultation, they are usually impacted. The treatment includes the administration of three enemas per day to disimpact (see the image below) or, sometimes, a bowel preparation with a balanced electrolyte solution.

Laxatives should not be given to a patient who is fecally impacted, because they may provoke vomiting and severe crampy abdominal pain. In addition, these symptoms cause the patient to become reluctant to take laxatives in the future. Therefore, the colon must be empty before laxatives are started.

Postdisimpaction administration of laxatives and enemas

Once the patient has been disimpacted, an amount of laxative (usually a senna derivative) is given, determined on the basis of the information the parents provide regarding the previous response to laxatives, as well as on the size of the colon on contrast enema. A dose is chosen, and the patient is observed for 24 hours. Water-soluble fiber is added to provide bulk and make the laxative more effective.

If the patient does not have a bowel movement within 24 hours following laxative administration, the dose was insufficient. The amount of laxative is then increased, and an enema is also administered in order to remove the stool produced during the previous 24 hours. The basic rule is that the stool in these patients with extreme constipation should never remain in the rectosigmoid longer than 24 hours, because it becomes hard and is more difficult to expel in the following days.

The routine of increasing the amount of laxatives and administering an enema every night until the goal (ie, the production of bowel movements and the complete emptying of the colon) is achieved is continued.

Radiography is performed on the day in which the patient has a bowel movement (which is usually with diarrhea) to ensure that the bowel movement was effective, meaning that the patient completely emptied the rectosigmoid. If the patient passed stool but did not completely empty the rectosigmoid, the amount of laxatives should be increased.

Occasionally, in the process of increasing the amount of laxatives, patients may vomit before any positive effect is achieved. In these patients, a different medication may be tried to see if it is better tolerated. Usually though, this means that the patient needs a colon resection.

Some patients vomit all types of laxatives, feel very sick, have severe cramps, and are never able to reach the amount of laxative capable of producing a bowel movement that empties the colon. Such patients are also candidates for surgical intervention. Usually, though, it is possible to find the dosage that the patient needs to empty the colon completely, as demonstrated radiologically. Once that amount has been reached, the patient can generally be expected to stop soiling.

After the family and the patient have been given a few days or weeks to evaluate the quality of life that they have with this treatment, the option of surgery can be discussed. An operation that provides symptomatic improvement is available and occasionally allows the patient to discontinue laxative administration and live a normal life.[8]

Indications for Surgical Therapy

Bowel management is indicated in patients with fecal incontinence after surgical repair of imperforate anus or Hirschsprung disease. It is also used in patients who are continent after surgical repair but suffer from constipation. Surgical therapy is occasionally used.[9] The two procedures described for bowel management are colonic resection and access for antegrade enemas.

Certain patients may be candidates for sigmoid resection. This procedure is indicated in a small subset of patients with massive dilatation of their rectosigmoid, in whom a bowel management regimen has been successful. The goal of the resection is to reduce the amount of laxatives required to empty the colon on a daily basis and thereby to improve the patient’s quality of life.

Access for retrograde enemas is obtained to change the route of enema administration. At a certain age, patients desire more independence for their enema administration and want to avoid the rectal route. To this end, an appendicostomy may be placed in the umbilicus, allowing patients to administer enemas themselves. Ideally, this procedure is performed only after a successful bowel management regimen has been implemented. A right-lower-quadrant appendicostomy or a cecostomy tube can also be sued for this purpose.[10]

Patients in whom resective therapy is considered to assist with bowel management must be fecally continent with a bowel management regimen. Resection of part of the colon in a patient with fecal incontinence can worsen the condition from a tendency to form solid stool to a tendency to make loose stool. Patients with incontinence and loose stool are much harder to manage than those who can form solid stool.

Therefore, sigmoid resection is only used in patients who can voluntarily empty their colon, albeit with massive doses of laxatives. These patients require much smaller doses of laxatives after the surgery.

Occasionally, removal of some of the colon does help a patient on enemas if the enema is given in a very high volume or requires significant additives.

Sigmoid Resection

Sigmoid resection may be indicated in a small subset of patients who are continent but have a huge laxative requirement. In this group of patients, if a megasigmoid is revealed on the contrast enema or determined by colonic manometry, a sigmoid resection can be performed to reduce the laxative requirement and improve quality of life. The most dilated part of the colon is resected because that part of the colon is believed to be most seriously affected. The nondilated part of the colon has normal motility and is anastomosed to the rectum. The very distal rectum is preserved. This can best be done laparoscopically.

Generally, the patients who improve the most are those who have a more localized form of megarectosigmoid. Patients with more generalized forms of dilated colon do not respond as well to resective therapy. They may require a resection of a longer segment of colon.[11]

Complications of a colonic resection include a leak at the anastomosis. This complication is the same as that which is typically faced in colon resections for other clinical situations.

Appendicostomy or Cecostomy

In patients who are fecally incontinent, a bowel management program with a daily enema is the ideal treatment. The rectal route may be problematic in older children who require enemas: They tend to seek independence and do not want their parents to give them enemas. In these patients, a continent appendicostomy (Malone procedure) or cecostomy for antegrade rectal washout can be performed.

The operation involves connecting the appendix to the abdominal wall and fashioning a valve mechanism that allows catheterization of the appendix but avoids leakage of stool through it. Some authors insert a cecostomy tube, which requires a synthetic tubing material that enters the cecum for the same goal of performing enemas. Both procedures have been laparoscopically performed. If the patient has had the appendix removed, a neoappendix can be created with a cecal flap.

Regular follow-up and reassessment are necessary. Often, the volume of enema must be adjusted. Abdominal radiography helps the surgeon assess the actual cleanliness of the colon.

Complications of appendicostomy include stricture and leakage, which usually necessitate a revision of the stoma.

0 التعليقات:

Post a Comment